Seeking An Identity:

In One Village, Three Generations Fight For The Past – And Their Future

Are they aboriginals with a culture to match, or are they modern Sri Lankans with an international outlook? A community caught between culture and development.

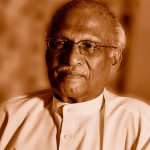

In Nallur, 68-year-old local man, K. Mailvaganam, is proud to introduce himself as an aborigine, an original resident of Sri Lanka. And as unofficial head of his local community, he declares that his community is not Tamil, as it is often classified. Rather they are descendants of the original inhabitants of Sri Lanka.

Meanwhile another local woman, Sangeetha, who is 25 and a lot younger, is busy trying to remove this aboriginal label from her family.

The fact that the two individuals have such differing attitudes toward their history and the history of their community, demonstrates the struggle between community development and cultural preservation that is playing out among the original Sri Lankans.

Both parties have good reason to fight for their side and both arguments are honourable. Which makes this situation all the more difficult.

The heritage that Mailvaganam claims is that of the so-called “sea aborigines”. The community was resettled on the coast and later, due to official ignorance and possibly racism, they were simply re-classified as Tamils.

“But we are not Tamils or Hindus, we are aborigines,” insists the Nallur aborigine’s community leader Nadarasa Kanagaratnam. It used to say “aborigine” in the place where race is filled in on the birth certificates of his community. Now they all just say “Tamil”.

“Our generation has just been turned into Tamils with the stroke of a pen,” Kanagaratnam says. “This is a huge injustice”.

/

Not everyone agrees with that. Sangeetha, for example, doesn’t think her children should be forced to be aborigines if they do not wish it. Although her ancestors worshipped different gods, she doesn’t see why her children should be forced to do the same.

“Although we have shouted to anyone who would listen that we are aborigines, what does it get us?” Sangeetha asks. “Next to our village is a real aboriginal village. All they do is go begging.”

“Our great-grandparents worshipped the trees and the rocks. The next generation worshipped other gods. But now many of us are Christians. We live like humans, not animals. But some do not like this. They don’t know there is a world beyond this village,” says Sangeetha, who fled Sri Lanka as a child because of the civil war and lived in India for many years.

The civil war and the tsunami disaster of 2004 have also had an impact on the villagers, says the chairman of the Pathalipuram Village Development Society, Gunasekaram Mailan.

Mailan’s family did not convert to another religion and Mailan now works for an NGO.

“As soon as the civil war ended, representatives of other religions came to our villages,” he explains. “They took advantage of our people’s poverty and their ignorance, and they converted them to other religions. The village now has three different churches, all of which get funding from overseas while our community gets no money. We become dependent on the church money even though we want to stay true to our community roots. Even my sister has converted!” he says helplessly. “Why can’t we develop and move forward, without having to compromise our identities?”

Mailan gives the example of the village of Nilankeni, which was badly damaged in the 2004 tsunami.

The people there fished using spears and collected honey. “We carried an axe on our shoulders and we did so proudly,” Mailan says. “Now our children carry a phone by their ears. All that happened after the tsunami. Our old village was near the sea but a religious organization came and rebuilt the houses, further from the coast. Our children were taken to boarding schools and educated. That was fine – but their religion has also changed. Now the parents are Hindu and the children are Christian. These children don’t have any interest in protecting our community heritage. And,” Mailan concludes, “all this was done by the relief organizations. They built churches in a village where there used to be only temples.”

Other locals have complained that often Sri Lankan villagers are enticed to go overseas to work, because the money for manual labour is better there. And when they come back, the critical locals say, they have converted to Islam.

Of course, it is an individual’s right to choose whether they want to make a change like this or not. And there are arguments both for and against any chosen change. But what cannot be condoned is when an individual comes under pressure to change.

“I cannot deny that our community needs to develop,” agrees Kanagaratnam. “But our community must also be protected.”

Some sort of mediation is obviously required. The younger generation is already grappling with these issues.

Sangeetha’s only daughter, S. Jacintha, 13, is studying at the local Tamil school. But she dreams of being a teacher.

“But our village school cannot help me with that,” Jacintha says. “Nobody from our school has ever gone on to do such a job. But the pastor at the church says he could send me to a big school in Trincomalee next year. I am waiting to wear nice shoes and a school tie and go to a new school.”

Which makes you wonder: When Jacintha’s dreams meet those of the community leaders’, who want to preserve their community, whose dreams will win?